UKIP started out as the Anti-Federalist League, founded by Alan Sked in 1991 in response to the proposed Maastricht Treaty. Other founders included Helen Szamuely, a Soviet-born British historian, Gerard Batten a future leader, and former Conservative Party member, Nigel Farage. The League was renamed UKIP in 1993 at a time when Eurosceptic politics was dominated by James Goldsmith’s Referendum Party. Sked was also a founding member of the Bruges Group and an academic lecturing at the London School of Economics. Himself a moderate, Sked resigned following the 1997 General Election, citing party infighting and far-right influences preventing it from broadening its appeal. Seventeen years later, in a 2014 interview with The Guardian, Sked would state that the de facto leader of UKIP since 1999 had been Nigel Farage, even though formally his first period as leader did not begin until September 2006. Craig Mackinlay, who would go on to become a Conservative MP for the South Thanet constituency after defeating Nigel Farage at the 2015 General Election, took over as acting leader of UKIP while a leadership election took place.

Holmes leads during period of infighting

Michael Holmes was elected party leader in September 1997 and served until 22 January 2000. He was one of three successful UKIP candidates at the 1999 European Parliament elections, winning a South West England seat. UKIP secured 6.5% of the popular vote at these elections, a major step forward from the 0.3% it had gained at the General Election in 1997.

Holmes’s tenure as leader was marred by infighting between his supporters and those of the party chairman, Nigel Farage, who had also been elected as an MEP. In an attempt to assert control, Holmes fired his deputy, Craig Mackinlay and party secretary, Tony Scholefield. These firings rebounded on Holmes, as a vote of no confidence was called soon after and upheld at the 1999 party conference. In January 2000, he resigned as leader and was replaced by Jeffrey Titford, the third of the trio of MEPs elected the previous year.

Like Farage, Titford had been a member of the Conservative Party, at one time representing the party as a councillor in Clacton-on-Sea. Titford’s time as leader was moderately successful, with its main electoral test coming at the 2001 General Election, where the party managed to field 428 candidates. However, the number of candidates did not lead to a breakthrough in national support, with the party securing just 1.5% of the vote (390,563 votes), well behind its showing in the 1999 European elections. Titford stepped down as party leader in October 2002 to give his successor ample time to prepare for the 2004 European Parliament elections.

The 2004 European Elections

It was Roger Knapman who succeeded Titford to lead UKIP into the 2004 European elections. Knapman had served as the Conservative MP for Stroud between 1987 and 1997. He served as a Parliamentary Private Secretary (a junior government role) but resigned in 1992 in protest at the Maastricht Treaty. Shortly after losing his seat in the 1997 Blair landslide, he joined UKIP and had risen to the leadership by October 2002. It fell to Knapman to lead the party into the 2004 European elections, with the party hoping to build on its 1999 return of three MEPs.

The 2004 European elections were a major breakthrough for UKIP, with the party securing 15.6% of the vote and 12 MEPs. UKIP finished in third place with 2,650,768 votes, ahead of the Liberal Democrats. The far-right British National Party received 808,201, but fell just short of returning an MEP. In later years, Nigel Farage would point to UKIP’s depriving the BNP of representation as evidence of his effectiveness in tackling extremism. After the election, UKIP was represented in Strasbourg by Roger Knapman, Robert Kilroy-Silk, Ashley Mote, Mike Nattrass, Jeffrey Titford, John Whittaker, Tom Wise, Graham Booth, Godfrey Bloom, Gerard Batten, and Nigel Farage.

At the 2005 General Election UKIP fielded 496 candidates but they could not replicate their success of a year before with just 2.2% of the vote and no MPs. Knapman contested the Totnes seat coming 4th with 7.7% of the vote. In 2006 he announced he would not be seeking another term and that there would be a leadership election with a new leader announced in September of that year.

Farage’s first leadership term

Farage took the reins on 12 September 2006 having already been a senior figure in the party, including Chairman, for fifteen years. The MEP for south-east England easily beat his nearest rival, Richard Suchorzewski, by 3,329 votes to 1,782. Farage had performed well when standing in a 2006 byelection for the Bromley and Chislehurst constituency where he had beaten future Chancellor Rachel Reeves into fourth place while securing 8% of the vote. Farage’s leadership pitch was his intention to change the party from a single-issue one to one with broader appeal. Under his leadership UKIP gained more media coverage and his term culminated in a successful 2009 campaign for the European parliamentary elections. UKIP’s 16% vote share and 13 seats edged up on their 2004 result under his predecessor. Two BNP candidates had also been elected. UKIP meanwhile formed a new bloc in the parliament with the hard-right Northern League of Italy.

On 4 September 2009, Farage announced that he was stepping down as UKIP leader to focus on his candidature for the Westminster Buckingham constituency where the incumbent was John Bercow, Speaker of the House though subsequent comments made to The Times journalist Camilla Long suggested he had grown weary of party infighting. He left the leadership on 27 November 2009 and was succeeded by Lord Pearson of Rannoch, a former-Tory peer nominated for his peerage by Margaret Thatcher. He would lead the party into the 2010 General Election. Farage stayed on as leader of UKIP’s MEPs in Strasbourg.

General Election 2010

The 2010 General Election offered UKIP another opportunity to translate its success in European elections into Westminster representation. The party fielded 558 candidates but could only secure 919,546 votes (3.1%) and no seats. Farage managed to come third in Buckingham with 8,410 votes (17.4%) a share flattered by the absence of Conservative, Labour, and Liberal Democrat candidates. Mr Farage was injured in a light aircraft crash on 6 May – the day of the general election. In August 2010, Lord Pearson announced his intention to step down, declaring that he “was not much good at party politics”. He had been in post less than a year.

Farage’s second term

Following Pearson’s announcement a leadership contest was organised with a postal ballot of all 18,000 UKIP members. Farage threw his hat in the ring as did fellow MEP Campbell-Bannerman, economist Tim Congdon and ex-boxer Winston McKenzie. Farage took 60% of the vote and began his second term at the helm of the party on November 5th. At this time Euroscepticism had been growing in the Conservative Party with as many as half of the new 2010 intake of 148 Tory MPs being in favour of leaving the bloc. Eighty-one Tory members defied the government in a vote related to an EU referendum. The following year, more than 100 Tory MPs attended a Eurosceptics meeting that foreshadowed the founding of the European Research Group. These Eurosceptics were constrained by the political reality of coalition government that relied on the support of the pro-EU Liberal Democrats lead by deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg.

UKIP’s high watermark

Farage realised the divisions within the Tory party represented an opportunity for UKIP and he targeted major gains at the 2014 European elections. Both coalition parties were losing popularity at the time, particularly the Liberal Democrats who were punished for entering into the coalition. The results were a triumph for UKIP and for Farage personally, with the party topping the poll with 26.6% of the vote increasing their group in the European parliament to 24. It was the first time a party other than the Conservatives or Labour has won a national election for 100 years. With some justification, Farage declared it “the most extraordinary result” in British politics in the past century. The leader of the far-right BNP, Nick Griffin, lost his seat and the English Democrats also saw their vote share fall. Farage announced the next target would be to secure a seat in Westminster and an opportunity soon arose with the Newark by-election held on the 5th of June 2014.

Early expectations were that Farage himself would stand for UKIP in Newark. Farage told the BBC that he was seriously tempted but the following day announced he would not stand. Instead UKIP put up MEP Roger Helmer. The byelection had been caused by the resignation of Tory MP Patrick Mercer amid a cash for questions scandal. While the Tory vote fell, the party still held off UKIP’s challenge with a 7,400 vote majority. UKIP’s 25.9% vote share was by far it’s best performance to date for a Westminster seat.

EU referendum on UK political agenda

The 2015 general election turned out to be a crucial one for the Eurosceptic movement in the UK. Back in January 2013, faced with internal party opposition prime minister David Cameron sought to bolster his position by offering an in-out EU referendum should the Conservatives form a majority government after the next election. Opinion polling in the run up to the election suggested a tight Labour-Tory race with the Liberal Democrats punished for participating in the Coalition. surprisingly, Cameron emerged with a small but workable majority of 10 seats. Despite the offer of the referendum, UKIP gained 3,881,099 coming third with 12.6% of the vote. The first past the post system meant the near four million votes translated to a single seat with the party’s candidate for the Clacton-on-Sea seat, former Tory MP Douglas Carswell, being returned. Farage had stood in South Thanet where he had recorded a 32.4% vote share, losing, ironically, to the Tory candidate and former UKIP leader Craig Mackinlay.

In line with his pledge, David Cameron announced on 20 February 2016 that a remain-leave referendum would be held that summer and that his government would be supporting the remain side.

Leave.eu and the referendum campaign

The campaign for the 2016 EU Referendum is one of the most well-documented episodes in British political history and does not require repeating here. For UKIP and its then leader Nigel Farage, it was the crowning achievement of the party’s twenty-five-year history. However, the leave campaign was beset with disagreements, most notably between the officially designated campaign group Vote Leave, and Farage’s alternative Leave.eu. Despite the lack of unity, UKIP and Farage, supported by donors like Aaron Banks, played a key role in the campaign, focusing on immigration and sovereignty.

Post-referendum UKIP

If the victorious Leave vote on June 2016 was the pinnacle of UKIPs influence on UK politics it was also arguably the beginning of its fall from relevance and certainly the end of its electoral popularity. On Farage held a press conference where he announced his decision to stand down as party leader, telling reporters, “During the the referendum I said I wanted my country back, now I want my life back.” He added; “The victory for the ‘leave’ side in the referendum means that my political ambition has been achieved. I came into this struggle from business because I wanted us to be a self-governing nation, not to become a career politician.” He retained his position as leader of the party’s MEPs in Strasbourg. After a short period as acting leader, his successor was named as Paul Nuttall at the party’s November conference.

UKIP had performed well at the Stoke-on-Trent Central by-election on 23 February 2017 coming second on 24.7% of the vote. Less positively, on 25 March 2017, UKIP’s only MP, Douglas Carswell, announced he was leaving the party to sit as an independent MP. At the 2017 local elections, UKIP performed poorly and in Kent it lost all 17 of its council seats. At the 2017 General Election, UKIP fielded 387 candidates. It was a poor election for the minor parties with a combined 82.3% of votes going to the Conservatives and Labour. That said, UKIP’s 1.8% vote share was a considerable disappointment with Nuttall resigning the leadership soon afterwards. At this time, UKIP retained its significant presence in the European Parliament under Farage’s leadership.

Scandals and Mass Resignations

Nuttall was replaced by former Liberal Democrat Henry Bolton, for whom Farage had acted as political referee. Bolton’s tenure was short, mainly due to his colourful private life, most notably his affair with a party member, Jo Marney, who was 30 years younger than him. The pair found themselves embroiled in a scandal over Marney’s controversial social media posts on Grenfell and Meghan Markle that some described as racist. The MEP Johnathan Arnott resigned from the party, labelling Bolton as unsuited to the role. On 21 January 2018, the National Executive Committee passed a vote of no confidence in Bolton. On 22 January, Margot Parker resigned as deputy leader. With Bolton refusing to resign, an extraordinary general meeting of the party was held on 17 February when 63% of members supported a vote of no confidence.

The brief but eventful Bolton leadership was followed by further tumult under Gerard Batten who, like Farage, had been a founding member of the party a quarter of a century earlier. On 14 April 2018, Gerard Batten was elected unopposed as leader. The early months of Batten’s leadership showed promise with a growth in membership and rising poll ratings. However, Batten proceeded to take UKIP down an anti-Islam path, culminating in his appointment of Tommy Robinson as a party advisor. This move was widely disliked by senior figures in the party and led to mass resignations. Nigel Farage quit the party on 4 December 2018 saying, “[Mr Batten] seems to be pretty obsessed with the issue of Islam, not just Islamic extremism, but Islam, and UKIP wasn’t founded to be a party fighting a religious crusade”. Catherine Blaiklock also resigned and in January 2019, she registered The Brexit Party Limited with Companies House. On 12 April 2019, Nigel Farage announced the launch of The Brexit Party and on 15 April 2019, three UKIP MEPs announced their intention to sit as Brexit Party MEPs for the remainder of their terms.

European Elections 2019

With the existential threat posed to UKIP by Farage’s new party UKIP faced losing its MEPs at the European elections of 2019. Theresa May was struggling to get her Brexit deal through parliament and Farage was now calling for a no deal exit. By the time of the election, 14 former UKIP MEPs had already switched to Farage’s new party. By the time the counting was over their number would swell to 29. The Brexit Party won the popular vote with a 30.5% share. UKIP, whose 24-strong contingent had shrunk to just 3 on dissolution, polled just 3.2% losing all their seats. Nevertheless, Batten announced he would stand for another term as leader, a move blocked by the National Executive Committee which passed a resolution that Batten had ‘brought the party into disrepute’. His leadership ended on 2 June 2019. Richard Braine, Batten’s preferred candidate, was elected leader on 10 August 2019.

The alleged data theft affair

In October 2019, Braine was suspended from UKIP after being accused of stealing data from the party, along with three other members: Jeff Armstrong, Mark Dent and Tony Sharp. UKIP went on to pursue a legal claim against the four which was struck down for lack of evidence. After less than 3 months in the post, Braine resigned on 29 October 2019, citing internal conflicts. At this time, UKIP was reported to be rapidly losing members at a rapid rate to Farage’s Brexit Party. Patricia Mountain became interim leader from 16 November 2019 to 28 April 2020. Freddy Vaccha was appointed to lead the GE campaign.

General Election 2019

The 2019 General Election was Boris Johnson’s ‘Get Brexit Done’ election. Nigel Farage stood down Brexit Party candidates in all the seats the Tories had won at the 2015 election. Meanwhile, UKIP stood just 44 candidates, gaining a vanishingly small 0.07% of the vote. Freddy Vaccha became leader on 22 June 2020 promising a “return to our libertarian freedom-loving principles”. However, more chaos ensued when after less than 3 months, party chairman Ben Walker announced that Vaccha had been suspended and Neil Hamilton was appointed interim leader in his place. Threats of legal action ensued, though with the Covid pandemic causing lengthy court delays, Vaccha relented and resigned from the party. As a result of Boris Johnson’s majority, the UK left the EU on 31 Jan 2020.

The Post-Brexit Years

With Brexit done, UKIP searched for a new purpose and achieved a degree of stability under the leadership of Neil Hamilton, the former Tory MP. After a spell as interim leader, Hamilton was confirmed in the role in October 2021. Hamilton had previously been elected UKIP’s leader in the Welsh Assembly, defeating Nathan Gill. By 2021, Hamilton was UKIP’s only representative at any level above local government, with no MPs, no representation in the Scottish parliament and just himself in the Welsh Senedd. In a sign of its dwindling membership, just 631 votes were cast for the party leadership contest in which Hamilton was successful.

Hamilton’s career in politics had been a controversial one and many saw his presence at the head of the party as unhelpful for attempt to unite an increasingly splintered right wing of British politics now comprising Reform UK, UKIP, David Kurten’s Heritage Party, Lawrence Fox’s Reclaim, the English Democrats, the SDP, the National Housing Party, among others. Neil Hamilton stepped down as the leader of UKIP in May 2024 to “spend more time with his family”. He was replaced by Lois Perry and made honorary president of the party. Illness cut short Perry’s time as leader, but not before she had caused controversy by backing Reform candidates for the 2024 General Election. She would claim in a subsequent media interview that there were “sinister” developments occurring in UKIP, taking it in an Islamophobic, homophobic and anti-Semitic direction. At the General Election, UKIP fielded 24 candidates, registering just 6,530 votes.

Nick Tenconi and the Lurch to Christian Ethno-Nationalism

Lois Perry had appointed Nick Tenconi as her deputy during her brief tenure as leader. Tenconi, who had operated a personal training business in Reading, had started his political activism as a senior official at Turning Point UK, an offshoot of Turning Point USA, the late Charlie Peters’ conservative Christian political action group. Tenconi became particularly associated with protests outside venues hosting drag acts. UKIP under Tenconi and its chairman Ben Walker has moved away from electoral politics and toward street activism, including protests outside hotels used to accommodate asylum seekers and marches advocating mass deportations.

Final thoughts

At its height, UKIP was able to muster the support of nearly 30% of the UK electorate in elections for the European Parliament. It was never able to repeat this success in Westminster, partly due to the first-past-the-post voting system. The trajectory of the party from its founding by Alan Sked as the Anti-Federalist League in 1991 to the current manifestation under Nick Tenconi has undoubtedly been a rightward one. It’s also true to say that it has experienced decades of political infighting and few periods of stability with a number of scandals thrown in for good measure. The party now fights for elbow room in a crowded space of small right-wing parties nestled to the right of Nigel Farage’s Reform UK. With its days as an electoral force behind it, it now focuses on street protests.

Recommended reading

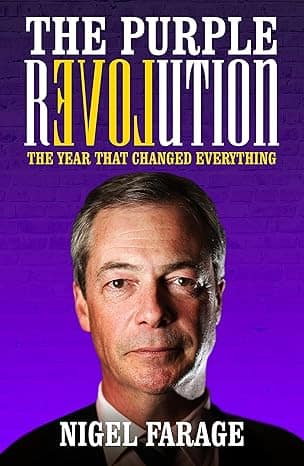

The Purple Revolution by Nigel Farage

Nigel Farage’s The Purple Revolution is an unapologetic and lively account of his rise from City trader to leader of UKIP and figurehead of British Euroscepticism. Written in his trademark blunt, humorous style, the book offers insight into his political philosophy, personal battles, and disdain for the political establishment. Farage presents himself as an outsider challenging a complacent elite, with anecdotes that are engaging if occasionally self-congratulatory. While critics may find it light on policy depth or introspection, The Purple Revolution succeeds as a revealing political memoir and an illuminating portrait of Britain’s populist turn in the early 21st century. Shop on Amazon here (Ad).

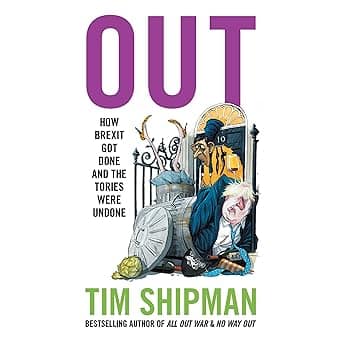

Out: How Brexit Got Done and the Tories were Undone by Tim Shipman et al.

“Out: How Brexit Got Done and the Tories Were Undone” by Tim Shipman delivers a sharp, behind-the-scenes chronicle of the chaotic endgame of Brexit and the Conservative Party’s unravelling. Drawing on insider access, Shipman and his team expose the political calculations, betrayals, and power struggles that shaped Britain’s exit from the EU. The book is gripping, meticulously sourced, and refreshingly candid, offering readers both drama and insight into modern British politics. It balances narrative pace with analytical depth, making complex events accessible without oversimplifying. A must-read for those seeking to understand the real forces behind Brexit’s messy triumph. Shop on Amazon (Ad)